Decentralization

Introduction

Decentralization is a concept that historically describes local governance structures where the responsibilities of planning and decision-making are not made by a centralized authority, but rather distributed throughout its membership. Although the terms ‘centralization’ and ‘decentralization’ were not coined until the 19th century in relation to significant political upheaval across Europe, the concepts have existed since the very inception of society. In spite of the obvious benefits of decentralization regarding inclusivity, representation and personal freedom, human history has primarily been a study in centralized authority because of the benefits it provides in efficiency in making decisions and its ability to be effective over large geographic areas.

However, recent technological advancements have allowed for decentralized principles to be utilized more effectively and many of the historical limitations are no longer applicable as robust mechanisms of governance utilizing decentralization are now available. In particular, blockchains have emerged as an opportunity for the development of new systems that more effectively embrace the benefits of decentralization as both a mechanism for member representative governance models and as a choice for users to access and develop application functionality within a decentralized economy.

While the historical definition of the term is still useful as a comparative measure to centralization, the term ‘decentralization’ itself has become synonymous with certain features of blockchain technology and a point of analysis in determining their technical, legal, economic and political function. Although there is still no unified singular definition of decentralization, the utilization of the term within blockchain generally carries certain characteristics that trace back the original Bitcoin whitepaper.

While the term decentralization is not explicitly found within the whitepaper, the ability to construct organizations and processes with “no central authority” absent a “trusted third party” for transaction or otherwise interacting with others has established a stand alone concept utilized within the industry. Developments in the application of decentralized technology, regulatory actions, legal analysis, economic potential and political theory have provided additional context for what decentralization means as it pertains to public blockchains and the applications built on top of these blockchains.

The goal of this paper is to help clarify why people in the broader crypto community organize around the concept of decentralization. Although a unified comprehensive definition would undoubtedly provide more clarity than the current contextual definition, the reality is that decentralization within the blockchain is an evolving concept and at this time, its utilization must be examined situationally to determine how the underlying processes fit within its current application. In this summary paper, we will explain the different components of decentralization, the benefits of decentralized systems, examples of how different projects have approached the process of decentralizing, and good-faith critiques of decentralization. This paper will act as a TL;DR summarizing the concept of decentralization within its current usage, while providing linked resources throughout for those interested in digging deeper into specific areas.

Note: This piece is not an attempt to reach an all-encompassing definition of the term ‘decentralization’ or an objective measure of project decentralization. Vitalik Buterin, co-founder of Ethereum, wrote a piece entitled “The Meaning of Decentralization” that highlights the difficulty of precisely defining the term. Attempts at measuring decentralization include: Miles Jennings paper about the principles and models of decentralization, Balaji Srinivasan’s post about the Nakamoto Coefficient; a Beijing Jiaotong University paper using various metrics to gauge decentralization; and Ketsal’s post describing open standards for measuring blockchain decentralization. Given the evolving nature of the space, we will publish updated versions of this document as the topic continues to evolve.

“Blockchains are politically decentralized (no one controls them) and architecturally decentralized (no infrastructural central point of failure) but they are logically centralized (there is one commonly agreed state and the system behaves like a single computer).” – The Meaning of Decentralization, by Vitalik Buterin (co-founder of Ethereum)

“Having decentralization as an end goal often means aiming for a vague, and possibly moving, target.” – Data Points to Measure Blockchain Network Centralization, by Josh Garcia and Jenny Lueng

Decentralization Standards for Layer 1 Blockchains

The core value proposition of many blockchains, including the Ethereum blockchain, is to act as a trustless infrastructure where developers can build immutable, decentralized applications. While other blockchains are working towards progressive decentralization, Ethereum’s first-mover advantage and wide adoption as the first smart contract platform — i.e, blockchains that natively enable smart contracts, allowing for a variety of composable applications to be built on top of the blockchain — makes Ethereum a natural benchmark for Layer 1 blockchain decentralization. Coinbase engineer Yuga Cohler went so far as to say that Ethereum’s upcoming transition to a Proof of Stake consensus mechanism will, if successful, “prove the viability of decentralization as a social organizing principle.”

Applications built on top of a Layer 1 blockchain inherit some of the decentralized attributes of the base layer, but just being built on top of a decentralized layer does not mean that applications are necessarily decentralized themselves. While the application inherits the immutability and censorship-resistance of the underlying base layer by default, each application makes design trade-offs that impact how decentralized the individual application is. In other words, the decentralized infrastructure layer provides a base where decentralized and centralized applications can work in conjunction, with each application and corresponding community making decisions as to what trade-offs to make to achieve their desired state of decentralization.

Ethereum’s level of decentralization is not without critique. Liquid staking derivative centralization and majority client risks have frequently been discussed as potential centralization risks for the Ethereum blockchain, and both of these critiques revolve around unintended centralized points of failure that could potentially arise in the future of the network. The specifics of these two concerns are outside the scope of this piece, but have been discussed at length elsewhere – for more information on liquid staking centralization, refer to this post on the risks of liquid staking derivatives by Ethereum researcher Danny Ryan and research from decentralized staking provider Lido. For more information on majority client risks, refer to this post by Ethereum researcher Dankrad Fiest and the Ethereum.org section on client diversity.

For the purpose of this post, the Ethereum blockchain can be considered a “sufficiently decentralized” infrastructure to serve as the foundation for a discussion of decentralization. The Bitcoin blockchain would certainly qualify as “sufficiently decentralized” as well, but by design, Bitcoin has less functionality embedded into the Bitcoin protocol compared to Ethereum’s more flexible smart contract platform. The Bitcoin community largely prescribes to an ethos of “simpler is better”, where Bitcoin itself is an expression of decentralization, since simplicity creates less vulnerability than more complex protocols. This post won’t get into the details of that argument, besides recognizing that Bitcoin would qualify as “decentralized enough” and that Bitcoin has been building out the Lightning Network to support more decentralized applications built on top of the network. Ethereum possesses a more robust application ecosystem from which to discuss the varying levels of application decentralization, but Bitcoin’s achievement as the first decentralized blockchain paved the way for the entire industry.

For more basic context on Ethereum specifically and blockchains overall, Bruno Lulinski, co-author of this paper, wrote A Simpler Guide to Ethereum that goes over an introduction to blockchains, DeFi, NFTs, the Ethereum community’s decision-making process, and the future of Ethereum scaling solutions.

The Different Components of Decentralization

Decentralization is essential to the value proposition of several parts of the broader crypto ecosystem, so it makes sense to view the meaning of the term relative to the area in which it applies. The elements of decentralization are both discrete (i.e, “is the project decentralized in this specific area?”) and related (i.e, “how does decentralization in one component impact a project’s attained decentralization in another area?”). Since decentralization in the context of one component means something different from decentralization in the context of a different component (while at the same time sharing underlying activity that impacts the other categories), projects need to consider each component to be able to function as intended.

The components of decentralization are broken into three broad categories that relate the effectiveness of decentralized systems across three axes; technical, economic, and legal decentralization. As Miles Jennings stated in his in-depth piece discussing principles and models of decentralization, “The effectiveness of these decentralized web3 systems will depend upon their security, economies and parity of information” – each of which corresponds to one of the three listed components.

- Technical decentralization – a global permissionless infrastructure layer and the applications built on top of it require credibly-decentralized technical underpinning. The underlying blockchain provides the execution layer for the on-chain components of the individual applications, but the applications themselves still require their own technical decentralization in the form of permissionless clients for interacting with the underlying smart contracts, user-owned data (and ease of data portability), and decentralized governance of the smart contracts by a broad group of participants in the form of a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO).

Questions to ask when considering technical decentralization – how are these systems designed? How are upgrades made, if needed? What processes backstop the execution of upgrades (i.e, Compound’s 48 hour timelock)? What blockchain underpins the application, and what tradeoffs does that blockchain force onto the application? Can users easily ‘ragequit’ the system — i.e, can users exit the system and use (or build) different methods of interacting with the core protocol?

From the perspective of determining the decentralization of the blockchains themselves — how many clients are there, and what’s the distribution amongst clients used for miners/validators? How can individual participants verify the authenticity of the given blockchain, and how difficult is it for an individual to participate in that verification process? There are many more ways to consider the technical decentralization of blockchains.

Ultimately, technical decentralization is the necessary foundation upon which economic and legal decentralization can occur.

- Economic decentralization – public blockchains create the opportunity for a reimagining of the economic interaction between the developers of an application and the users and adjacent stakeholders around that application. In the ‘traditional’ pre-blockchain world, companies are incentivized to view their users as a source of value extraction, primarily in the form of user-generated content or the corresponding data of the end user, which is then transacted between the company and willing advertisers behind the scenes.

Blockchains allow for systems that are not reliant on central leadership, allowing for the balancing of incentives between developers of the application, contributors to the application, and users of the application. These economically-decentralized structures are basically a new generation of open-source software communities, but with embeddable, transparent economies. In an economically-decentralized ecosystem, contributors can participate in the value-creation of the application while receiving compensation for their contributions.

Questions to ask when considering economic decentralization – how is the underlying token of the application designed and distributed? How was the airdrop designed, and what considerations were made by the early project developers to prevent centralized ownership of a majority of project tokens? How are early investors and project contributors compensated, and what do token lockups for all parties look like? How do distributions of the DAO treasury work; i.e, how are funds distributed to initiatives and/or working groups intended to further the project’s mission?

- Legal decentralization – beyond the technical mechanics and the economic benefits of decentralization are matters of regulation and legality, including taxation, liability, ownership, intellectual property, reporting and privacy. Although U.S. securities law is an essential area of analysis in determining how decentralized systems may make use of digital assets, it is not the only area of law impacted by the decentralization made available through public blockchains.

Although decentralization exists in the current legal system – most obviously in the form of general partnerships – there is significant question as to how the default rules established for participation and responsibility can be fairly applied to decentralized systems that are exceedingly dissimilar from the activity giving rise to existing law. Going beyond the superficial similarity to existing rules and laws, the decentralized activities available through the blockchain represent significant changes in concepts like equity, ownership and control. These differences underscore a different relationship and responsibility than the activity giving rise to current laws and regulations and create significant uncertainty in how decentralized organizations that exist on the blockchain will be treated.

As these activities are capable of creating taxable events and acting in a way giving rise to litigation, it is expected that taxation and liability will soon be matters of equal prominence with securities law when considering legal decentralization.

Early projects necessitate some form of central leadership and planning to define the project’s purpose and provide crucial activation energy. These teams might retain some influence in the soon-to-be-decentralized project, but the level of influence retained could have a significant impact on whether the project is considered decentralized from the perspective of regulators and other government authorities.

Securities regulation stems largely from a desire to prevent information asymmetry amongst market participants – while there currently is no defined standard for the concept of legal decentralization, the levels of influence that early project contributors retain in the decentralization process, as well as the transparency of information amongst participants, will be pivotal to determining whether a project is legally-decentralized.

Many have written high-quality overviews on the topic of decentralization from the perspective of securities regulation:

- Scott Kupor has written about the key regulatory questions in crypto and has described considerations for determining whether a token is a security;

- David Kerr and Miles Jennings authored a legal framework for decentralized organizations;

- Stephen Wink and Shaun Musuka described the pursuit of sufficient decentralization as a clear path to avoiding securities regulation;

Questions to ask when considering legal decentralization – how much influence does the early project team have, and where does that influence come from? Does their influence stem from outsized voting power retained in the supposedly-decentralized organization, or from their voice in communal decision-making processes? How much influence do early investors have? Can community members be held accountable by other community members, and does the project depend on the efforts of a central authority? Do different stakeholders have asymmetric information based on the structural design of the organization? More on legal decentralization in the securities law section below.

The Benefits of Decentralized Systems

As discussed above, the term ‘decentralization’ is itself a reflection of the term ‘centralization’. Looking at the attributes that a decentralized system might have, like censorship-resistance and distributed decision-making, makes it easier to visualize the concept.

Censorship-resistance

Censorship-resistance is the idea that no single governing authority can unilaterally make the decision to restrict another participant’s actions in a network. Historically, coordination between humans has relied on some levels of trust. Trading goods between two people requires the trust that both parties will actually deliver their goods to the other, and agreeing to some sort of truce or treaty between conflicting nations requires trust that the other party will continue to abide by the agreed-upon treaty.

Immutable code deployed on decentralized public blockchains sets the foundation for censorship-resistant, privacy-preserving innovation. These censorship-resistant systems are not yet completely un-coercible, but they act as a necessary foil to the institutions and platforms we’ve come to rely on outside of crypto (world governments, social media platforms, etc.). If the infrastructure layers (the blockchains themselves) weren’t decentralized, it would be simple for a powerful government to shut it down – just find the party responsible for the network and coerce them.

Decentralization makes this difficult, as China’s Bitcoin ban demonstrated, because censoring sufficiently decentralized systems requires coordination outside of the scope of most governments; just a few months after the China Bitcoin mining ban, several underground mining operations emerged in China to fill the gap left behind by the ban. NFTs have been used by individuals to preserve information in the face of authoritarian governments as well – however, these NFTs still required anonymity from the individuals to avoid direct coercion from their government. Even democratic governments like Canada have recently expressed a willingness to exert powers of censorship by coercing financial institutions to financially censor some citizens. Other countries, like Ukraine, have effectively used the censorship-resistant quality of public blockchains to fund their defense when cross-border money transfer companies initially capped transfers of money to Ukraine (these caps for transfers to Ukraine were later relaxed).

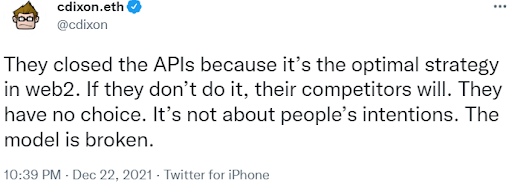

Tech giants like Apple, Facebook, and Google have scaled to huge amounts of power and influence, throwing them (willingly or not) into public debate about the interactions that happen on their platforms (and the processes that guide their frequently–controversial decisions). Twitter is frequently used by governments to communicate directly with their constituents, and offers a great example of the benefits of decentralization – in 2018, Twitter removed access to a variety of APIs that independent developers had used to build applications on top of Twitter.

A decentralized system would be censorship-resistant to decisions like Twitter’s. In fact, transparent, unopinionated rules to participation are by themselves a flavor of censorship-resistance that blockchain-based applications naturally inherit, since by default, code deployed to public blockchains is open-source. Even if Twitter’s former CEO, Jack Dorsey, had committed to an open protocol and long-term neutrality (as he later lamented), the promise of a censorship-resistant Twitter will always fall flat on long enough time horizons — it’s the natural game-theoretic conclusion. Open-sourcing code and permitting user ownership of private data are concepts that are fundamentally opposed to the business models of corporations built on closed protocols which rely on the data of their end users to generate financial returns for their shareholders.

Resilience to Attacks and Decorrelation

Vitalik Buterin argues that decentralized systems are more resilient to attack and less likely to accidentally fail than their centralized counterparts. Critically, decentralized systems are generally more expensive to attack due to the absence of sensitive central points of failure for attackers to target — an attacker couldn’t just infiltrate the Ethereum Foundation and press a big red “HALT” button (since there is no big red button), and an attacker couldn’t overpower Buterin and force him to shut down the blockchain (since Buterin doesn’t have that type of centralized power, despite being the initial founder and specwriter). At the application level, trust assumptions, key management and security practices will differ, which means different levels of resilience to attacks. The Layer 1 blockchain’s resilience to attack will still provide a credibly-neutral, permissionless infrastructure for application developers to build from.

Decentralized networks also tend to breed duplicative systems, leading to more robust security. Tim Beiko, one of the lead coordinators for the Ethereum developer community, recently called this benefit of duplicative systems “uncorrelated failure modes” on Farcaster. The general idea is that multiple solutions – i.e, different client implementations, different approaches to a specific problem, or just different schools of thought — reduce the probability of catastrophic failure across the stack.

(Beiko technically uses “decorrelation” and “uncorrelated failure modes” as a replacement for the term “decentralization” in this context, because of the difficulty of quantifying decentralization. We are using “uncorrelated failure modes” as a benchmark for a sufficiently-decentralized system. Therefore, from our perspective, a decentralized system would necessarily have uncorrelated failure modes, but either way, the sentiment is the same.)

An example of catastrophic failure at the hands of correlated risks is the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, where the risks created by the rise of collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps, and frothy lending practices were improperly underwritten by ratings agencies. This highly-tangled web of risks led to correlated failures as homeowners defaulted, leading to lender defaults, leading to counterparty defaults, leading to havoc.

Underwriting systemic correlated risks is difficult and, in complex interconnected systems, can lead to disaster. Decorrelation of systemic risks via the open borders of blockchains can help mitigate these risks and reduce the surface area of attack vectors.

“If you had asked a normal person in 2007: “How would it affect your life if it turns out that investors have mispriced the super-senior risk in synthetic collateralized debt obligations built out of subprime mortgage tranches,” that person would have said “I have no idea what you are talking about, but I can’t imagine how that collection of words would affect me.” But it did.” – Money Stuff, May 12, 2022, Matt Levine

Transparent incentives and distributed decision-making

While a shareholder in a public company might successfully petition the board of directors to include a shareholder proposal in an annual proxy statement, boards have some leniency in which proposals they have to include for discussion, and many large tech companies (Facebook, Snap, and Google, for example) have dual-class share structures that give insiders a supermajority of voting power, denying any significant outcome from stakeholders.

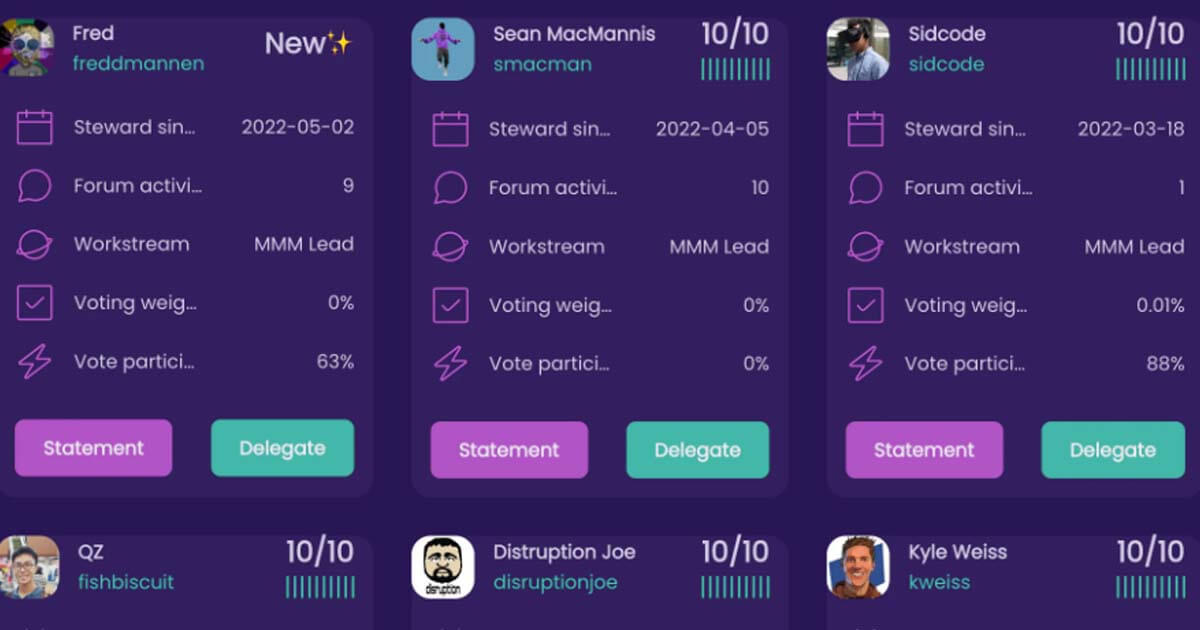

While not solely a tool for distributed-decision making, decentralized systems do enable governance transparency that has the potential to improve the equity and effectiveness of critical decision-making processes. There are good-faith critiques of distributed decision-making systems, including the necessarily-centralized focus required by early project teams, the tragedy of the commons, and the voter apathy that can manifest in these types of horizontally-distributed decision-making processes. Governance of these distributed decision-making systems is a complex topic in and of itself (which will be discussed in a future DAO Research Collective piece). However, proponents of decentralized systems argue that transparently-recorded actions are one of the main benefits of decentralized organizations.

How projects are decentralizing

For almost any complex project, a certain level of activation energy is necessary to get the project off the ground. Individual leaders driving change, rapid iteration cycles, well-informed roadmaps — projects that want to move forward with some momentum naturally find it near-impossible to be decentralized in any significant way in the early days. Jesse Walden wrote a useful playbook for progressive decentralization for founders in crypto.

The normal course of action for blockchain-based applications undergoing the process of decentralization today is roughly:

- create a governance token that gives holders the right to vote in some sort of directly- democratic process;

- distribute governance tokens, usually as an airdrop to past users and stakeholders based on specific criteria determined by the initial project team;

- invest in processes that relinquish the founding team’s control over the project, like creating a constitution to help navigate future challenges, forming internal working group structures, passing control of administrative controls and treasury management to the community of stakeholders, and providing a venue for stakeholders to participate in governance discussions.

Below, we will walk through a few examples of projects that have used different iterations of this general methodology to begin the continual process of decentralization. These case studies demonstrate the different ways that application-level decentralization can manifest.

Optimism and Hop

Optimism, a Layer 2 scaling solution built on top of Ethereum, recently announced their plan for decentralization by painting an ‘Optimistic vision’ for their future as a decentralized system. For Optimism, the decentralization process revolves around giving their network of users the administrative power to push upgrades, and creating a governance and operating structure. Optimism launched the OP token, which distributes ownership of the project to stakeholders based on a list of criteria, but critically, Optimism kept the door open for future planned airdrops (to disincentivize short-termism). Optimism also launched the Optimism Collective, “a new model of digital democratic governance”, and heavily emphasized public goods funding programs as a way to bootstrap an ecosystem of applications and users on Optimism.

Optimism leaned on transparency and vocal discussion with existing users during the decentralization process (which remains ongoing), releasing an Optimism Operating Manual, experimenting with a bicameral governance structure, and laying the groundwork for public goods funding within the Optimism ecosystem. Optimism emphasized the idea that funding public goods in the decentralization process is highly important, since without decentralization, public goods projects might not exist or might rely on a centralized entity to fund. Ultimately, while the participation of centralized entities in public goods funding should be applauded and encouraged, relying on only one central entity to fund public goods project leads to a risk vector – if funding for public goods is centralized, funding might only be distributed to projects that appeal to the centralized entity, which is by itself a form of censorship.

Hop, a bridge for assets between different blockchains, also recently announced their plans for decentralization, which included a standard snapshot of participation in anticipation of a token drop to community members. The most noteworthy aspect of Hop’s airdrop is Hop’s attempt to incentivize third-parties to specifically carve out Sybil attackers — fake accounts made in an attempt to game the airdrop system for economic benefit — by asking community participants to search for purported attackers and report them.

Hop included a 25% reward to those that caught Sybillers, with the remaining 75% distributed back out to every real participant receiving the airdrop. Hop acts as a case study for how projects might prevent bad actors from gaming the system, and how economic incentives can be the strongest motivator for distributed, decentralized communities. (Optimism later utilized a similar methodology for removing Sybil attackers).

One other project of note briefly worth mentioning is Juno, a smart contract network built on the Cosmos blockchain. While Optimism and Hop specifically implemented processes for fair distribution of their tokens, a poorly designed Juno airdrop was gamed, leading to a huge stake airdropped to one ‘whale’ user. The implication here is that, in part, the network could be less decentralized given this structural failure, with a lopsided amount of influence and decision-making power going to one user. The Decentralized Autonomous Organization that governs the Juno project later voted to confiscate the stake from the single user, but the Juno saga demonstrates the importance of thoughtful mechanism design in the decentralization process.

Uniswap and Sushiswap

Uniswap is arguably the most decentralized application in the crypto world today and the best example of a hyperstructure. Uniswap is a decentralized exchange — essentially, a set of smart contracts that allow anyone to trade crypto assets without requiring a trusted intermediary — and one of the first projects to airdrop a token to users.

In the midst of 2020’s DeFi Summer, Uniswap distributed 15% of tokens to past users, while reserving most of the remaining tokens for community member distributions. Governance of the Uniswap treasury was transferred to holders of the UNI token, who could decide the future of the protocol in a direct democracy governance process, and the Uniswap protocol is governed and upgraded by UNI token holders in the same process.

Interestingly, end users of the decentralized exchange don’t pay fees to UNI token holders, although governance holds the power to turn on the fee switch. This ‘fee switch’ mechanism has since followed into many other projects, and conversations about turning on the fee switch have been ongoing in Uniswap governance since the first few days after the initial airdrop. These discussions present an interesting insight into incentives and decision-making in decentralized governance systems.

If Uniswap’s governance actions were to halt for some reason, the smart contracts (deployed initially on Ethereum, but since expanded to other blockchains) would continue to run for as long as the underlying blockchain continues operating, without any additional human intervention. Uniswap also operates a centrally-managed front end to make it easier for users to interact with those contracts, but users can opt out of using the Uniswap-branded interface and can choose to interact with the smart contracts directly or create a new front end for interacting with the contracts.

SushiSwap, a decentralized exchange formed specifically as a community-owned alternative to Uniswap before the UNI airdrop, forced Uniswap’s hand towards (more rapid) decentralization. SushiSwap forked (i.e, replicated) Uniswap contracts, built a frontend around them, and vampire-attacked Uniswap by offering incentives for users to move over to SushiSwap’s exchange. This was done in tandem with a SUSHI token drop to Uniswap users, further incentivizing the user move from Uniswap to SushiSwap. Basically, SushiSwap launched with the premise of decentralization, showcasing how a decentralized-from-the-start project might launch. SushiSwap encountered significant challenges almost immediately with this approach, with the de facto project lead leaving the project, selling tokens, and ultimately returning the tokens.

The results from the vampire attack were both successful and unsuccessful. On one hand, SushiSwap was able to effectively bootstrap the community and network effects necessary for decentralized exchanges to operate by siphoning users from Uniswap. On the other hand, despite SushiSwap draining hundreds of millions of dollars in assets from Uniswap in 2020, Uniswap is still the most widely-used decentralized exchange in the world, bar none. Sushiswap, meanwhile, has dealt with significant governance issues over the past two years, and has floundered in recent months. Aaron Brown of Bloomberg Opinion said “The two basic problems with SushiSwap are too many opportunists in its initial creation and failure to align incentives carefully.”

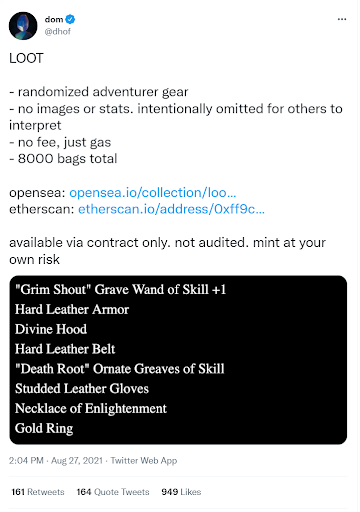

Loot

Loot, an NFT project that launched as just a single tweet from its’ creator Dom, took a different approach to project decentralization. Loot was deployed as a smart contract to the Ethereum blockchain with no fee for minting the NFTs. The collectibles themselves are short lists of ‘randomized adventurer gear’. Collectible holders were prodded to interpret the project freely, and because the project was deployed to a public blockchain — Ethereum again, in this case — others could build other stuff on top of the NFTs. The concept of Loot is further summarized in this thread by Avichal Garg.

Because of the free-to-mint mechanism and the low-touch launch, the ‘airdrop’ for Loot was more of an open buffet, where users that became aware of the project could opt-in to participation by minting a free collectible. Communities quickly organized around the project and began identifying opportunities to use Loot in their own creative interpretation of the project. Dom, in an effort to remove the possibility of any “figure or organization to ever act as its owner,” offered a proposal to Loot holders to burn the administrative keys to the Loot contract, creating a hyper-decentralized structure from Day 1.

The project immediately became the most interesting story in crypto and skyrocketed to $200M in trading volume within 10 days. Loot became a case study in collaborative value creation, with projects like Loot Character, Loot Mart, and an entire ecosystem of other projects springing up around Loot. As of mid-2022, the interest around the Loot project has waned, partially due to the launch of Synthetic Loot, a derivative created by Dom to limit the scarcity of the initial drop (which probably resulted in a decrease in the initial speculative behavior surrounding Loot). The lack of a central authority dictating initial project focus possibly impacted the future of the project as well, although these factors clearly sparked some of the initial interest in the project. Either way, it’s clear that Loot embodies the concept of project decentralization and remains one of the most innovative projects in the space. For a more detailed summary of the Loot project, Kyle Russell of TechCrunch wrote a good summary.

Critiques of decentralization

Despite occasionally being misconstrued as such, a decentralized economy built on public blockchains is not a replacement for all centralized entities. Instead, it is an expansion of structures that will allow decentralized and centralized organizations to interact in ways that previously were not technologically feasible or practical. Still, there are several good-faith critiques of decentralization in the context of public blockchains, which are addressed below.

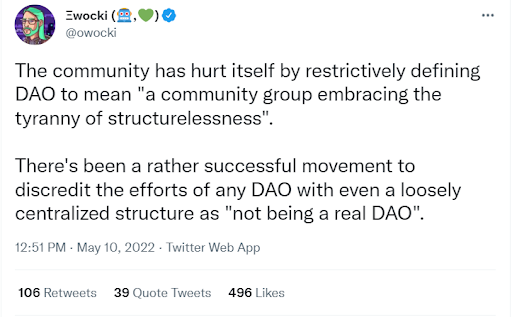

Only perfectly-horizontal structures can be considered decentralized

To some, the idea of decentralization means perfectly unhierarchial structures, completely unstructured and without guidance or leadership. Some critics of decentralization argue that any influence exerted in a decentralized system by a small number of participants proves that the system is centralized, or that any attempt at structure preserves centralization. This claim has been used to say that Ethereum isn’t decentralized. But as described throughout this piece, decentralization comes in various forms and must be viewed through specific frames of reference to distinguish between different types of decentralized systems.

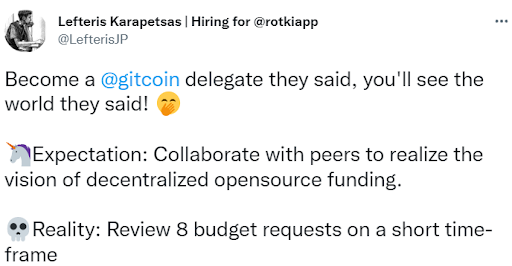

Kevin Owocki of Gitcoin discusses this in a Twitter thread where he points out that decentralization can refer to “decentralized governance via a permissionless token” rather than a “chaotic loose web of individuals”.

In Anticapture, Spengrah writes that “conflating decentralization with permissionlessness is one of the most common mistakes in the DAO space.” Spengrah discusses the concept of anti-capture, a framework for how networks of humans can design systems resistant to governance capture by bad actors. Capture-resistance governance is a more reasonable goal for decision-making for projects that can’t be reduced to completely non-human programmatic functions.

Centralized Entities Prove Centralization

The centralized entities that exist in the crypto world — like Celsius, a centralized exchange — are often used as a demonstration of how the crypto world is not truly decentralizing. This claim appropriately targets the projects that claim decentralization as a selling point to attract users to what is a clearly centralized (by any definition) project, including many of the recent catastrophes in crypto (Luna and Celsius, for example). These should be critiqued as such.

But as described in detail throughout this piece, decentralized systems are not just completely horizontally-distributed systems and instead, there are several individual components to consider when judging the level of decentralization of a project. Crucially, the critique that “centralized entities within the system prove centralization of the system” often ignores the idea of data portability. Mudit Gupta, Chief Information Security Officer of Polygon, called data portability “the ability to be decentralized.”

Centralized systems can exist and create value for end users by making it easier to interact with permissionless blockchains, but ultimately, blockchains give users the ability to exit with their own data. If OpenSea, a centralized NFT marketplace, decides to censor a subset of the NFTs that are sold on their platform (by not displaying them on the OpenSea user interface), or if OpenSea decides to start charging higher fees to users, users can simply stop using OpenSea and move to another NFT marketplace. OpenSea doesn’t actually hold user NFTs — OpenSea is just a venue for displaying and transacting (importantly, a venue with lots of liquidity, which makes for a more efficient marketplace and better price discovery, but a venue nonetheless).

(As a side note, OpenSea recently launched Seaport, a decentralized protocol to underpin their marketplace.)

Traditional internet companies don’t give users the flexibility of data portability because they’re not incentivized to do so, but blockchain-based applications necessarily have data portability embedded into their operations. While centralized crypto companies can create efficiencies (like organizing liquidity, providing customer support, and standardizing user interfaces), the user’s ability to exit the system provides a check on any centralized entities’ power over the system and ultimately, over its users.

Ineffective Governance and Potential Plutocracy

The critique that decentralization will beget ineffective governance might be the most truthful critique of the ecosystem right now. As of early 2022, governance of decentralized organizations is largely ineffective across the board — participation is low, and pure coin-voting, as most decentralized organizations have trended towards, has a variety of embedded issues that might create more plutocratic systems than the prior status quo.

The DAO Research Collective’s Governance paper will touch on many of these issues, and Fred Ehrsam of Coinbase / Paradigm wrote a prescient 2017 piece on blockchain-based governance systems that highlights some of the benefits and issues of on-chain governance, as well as future approaches. Ultimately, it remains to be seen whether decentralized governance can be as effective (or more effective) than traditional centralized governance systems.

“Only by making technical systems that offer a variety of mechanisms for checking concentrations of power and by simultaneously building social ideologies constantly on the lookout for failure modes of these mechanisms can we hope to succeed where previous attempts at decentralizing authority have failed.” – Liberation through Radical Decentralization, Vitalik Buterin and Glen Weyl

Conclusion

- Don’t overlook the importance of non-programmatic decentralization. Often, decentralization is taken to a logical extreme, where ‘true decentralization’ only applies when no human has any impact on the outcomes of the blockchain-based system. But social consensus and good-faith efforts to improve decentralized governance, while still striving for more effective governance systems, shouldn’t be ignored.

Above-and-beyond transparency in decision-making processes, intellectual honesty by community participants, forums for good-faith criticism and discussion — these are ways to encourage decentralization without removing the valuable human components of this ecosystem.

- Decentralization is our most important tenet. The benefits of decentralized systems, like censorship-resistance, data portability, and resilience to adversarial attacks, are crucial to ensuring the creation of a decentralized world that can exist (as Balajis Srinivasan stated) as “a healthy optimum between those with the recognition that different people will trace out different optima.”

- Many experiments are still ongoing! Albert Wenger’s recent post describes decentralized consensus as follows — “It is difficult to overstate how big an innovation this is. We went from not being able to do something at all to having a first working version.”

But to be clear, we’re still on the first handful of working versions. Optimism’s bicameral governance structure and emphasis on public goods funding, DAO-to-DAO mergers, Loot-like NFT projects — some of the most important developments in crypto right now are experiments on how to optimally create and govern decentralized systems.

It seems certain that multiple ‘implementations’ of decentralized systems will exist. With many experiments still on the horizon, decentralization is a topic that will continue to be pervasive in the crypto communities, and as the ecosystem continues to capture the zeitgeist and enter broader global discourse, decentralized systems will become more refined and pivotally important.

To reach this next stage of refined, globally-relevant decentralized systems, we as users and community stewards need to remain intellectually honest towards the desired goals of decentralized systems, and we must hold accountable those who infringe on the ethos of the ecosystem. When centralized entities act in bad faith under the guise of decentralization, we have to critique them publicly, and we have to design systems that allow for centralized and decentralized organizations to participate side-by-side in the ecosystem while communicating to users the design trade-offs that both types of organizations have chosen. Finally, we have to do better in terms of communicating the need for various implementations of decentralized systems to regulators, local representatives, and the broader public, with the goal of fostering credibly-neutral decentralized systems that can stand the test of time.

Acknowledgments

Authored by Bruno Lulinski and David Kerr.

Thank you to Connor Spelliscy, Jacob Robinson, and Mike Wawszczak for providing feedback on this paper, and to the DAO Research Collective for their help and support.

This article was originally published in The Defiant.