Status Games: Social Media and the Gamification of Value

Samuel Vance-Law

Principal Researcher, Decentralization Research Center

Cover Image: Last Stop Okinawa, via Pexels

1) Measuring Status Online: Like, Follow, Subscribe, Repeat

Status, unlike power or wealth, is a measure of social standing that must be conferred by others, and the Internet has enabled a plethora of quantifiable status measurements. Every time we like a video on YouTube, follow a friend on Instagram or a colleague on LinkedIn, upvote on Reddit, like a video on TikTok, or retweet on X, we produce quantifiable data on who or what we value in the online sphere. More passive measures of value are also constantly in play. When we listen to a song on Spotify, it gains a stream, we move up the author ranking on SSRN when someone reads our paper, viewing a video on YouTube, whether we like or subscribe or not, produces a metric of value. And these are only the measurements we can see. Almost every click we make online is logged and used as a measure of value by someone or some algorithm somewhere.

These measurements of value are, however, inherently flawed. Conferring status creates inequality by definition and quantifying it exacerbates that inequality. One might assume that quantifying status—seemingly making it clearer—would help reduce inequality. However, when status is transparently quantified, rewards become more unequally distributed, not less. In an experiment assessing the hypothetical allotment of bonuses, quantifying status increased the bonuses to the highest-status participants by a Gini coefficient of 30 percent. In another experiment in an artificial online music market, one set of buyers could see the numerical data of song downloads, while a control group could not. When numerical ranking information was available, inequality increased significantly. Critically, these advantages are cumulative. While initial differences may appear small, each interaction compounds the inequality. These advantages accumulate particularly quickly online. We engage in these types of evaluative systems dozens of times a day, whether liking a friend’s post, watching a video on YouTube, or simply clicking on a link, affecting both how people respond to one another and their content, and how algorithms determine which content to present and to whom.

2) Empty Content and the Gamification of Status for Profit

Complex information travels slowly and poorly; simple information travels quickly and far. In small communities, the complexity of information available can allow community members to assess value to that community. However, on social media platforms, information needs to be stripped of most of its complexity to travel quickly and widely to compete for attention and gain the status “points” of likes, followers, retweets, etc. While the offline world provides many examples of this type of simplification (evaluating a student based on their grade point average instead of reading through the entire body of their work, for example), the Internet exponentially increases this tendency. In order to prove value and therefore gain status, users simplify their output allowing their information to travel quickly and be immediately digestible. Underlying quality is hard to determine under these circumstances. Simultaneously, the options at our disposal to recognize and reward quality are also limited. The “like” we give to a post for a cure for an illness is the same “like” we give to a friend’s selfie because that “like” also has to travel quickly and be comprehensible to a large number of people. Both in creation and assessment, social media content contains little complex information, and the scale of interaction is too great to provide accurate measurements of value to a community.

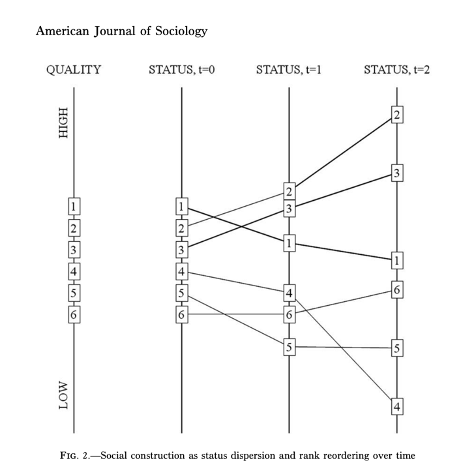

Status is based on perceived value, not value per se, and online systems do not simply over-reward people who provide the most value and under-reward those who provide less. Since we can all see the choices made by others, social influence is high and, where social influence is high, false information can overwhelm underlying quality: “A new, self-reinforcing reality takes over—a reality in which an individual would be hard-pressed to convince others that his status is not commensurate with his underlying quality.” These biases “can decouple status from quality” even when repeatedly challenged with demonstrations of quality. Paradoxically, the system to which we continuously add data in the effort to come closer to “accurate” attributions of value and status could be leading us farther away from being able to recognize “underlying quality” at all.

Figure 1 – “Social construction as status dispersion and rank reordering over time” (Lynn et al., 2009)

Status is teachable and it is sticky. Not only can status be taught by treating someone according to status beliefs, but third-party members witnessing the interaction will also acquire that status belief. Just the knowledge that others share a status belief leads people to conform to it, even if they do not personally endorse it, and even if they are personally disadvantaged by it. When people see others supporting a social order, “the order seems like a valid, objective social fact. Consequently, the individuals act in accord with that order themselves, even if they privately disagree.” And when the social order seems like an objective fact in one context, adopting it in further contexts requires little justification. It simply is.

These concerns would exist within a system publicly owned and operated for the public good. However, the vast majority of the Internet is not. Corporations have gamified how we evaluate one another to maintain our attention for profit. As such, the status games we play are not designed to be pro-social or accurate vehicles for assessing value to a society in general. Rather, they function for the profit of corporations. Furthermore, while computer games often have point systems that reward behavior that deviates from what we value in society, those measures of value and status are normally siloed within the game itself—the number of goals a player scores in FIFA 25 does not affect their employability as a nurse, for instance. However, a point valuation on X, TikTok, LinkedIn, et al. has material effects on the reputation and therefore employability of the participants in that game. A journalist with 15,000 followers has higher value than a journalist with 1,000 or 100, not only within the logic of the platform, but in terms of reach, advertising potential, and employment. That is to say, the measure of the value of a “good” journalist is no longer journalism, a musician musicianship, or a politician good governance. The measure of value is based on the ability to play various status games for corporate profit.

3) When Every Friend is a Dollar Sign: Decentralized Social Media Solves One Problem and Introduces Another

Two main problems have been identified above: the quantification of value to determine status, and the creation and ownership of these systems by for-profit corporations. Decentralized social media platforms attempt to solve the second of these problems by introducing equitably owned and governed digital spaces in which users can own their data, their digital identities, and sometimes the platforms themselves. There are many ongoing experiments in decentralized social media, including Bluesky (open-source, though not blockchain), Warpcast (on Farcaster on Ethereum), Mastodon (open-source, not blockchain), Ecency (on Hive [not Hivesocial]), Hey (on Lens), and Steemit, among many others. All of these platforms provide greater control and ownership to their users than traditional social media, through open-sourcing, blockchain, user ownership of data, or a combination of the above.

However, while they succeed in returning ownership and governance to their users, many use almost identical measures of value as their centralized counterparts, with some doubling down on some of their worst practices.

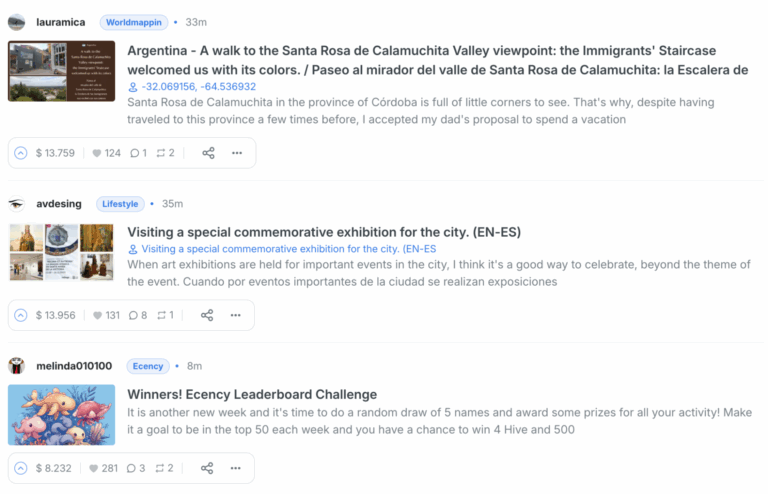

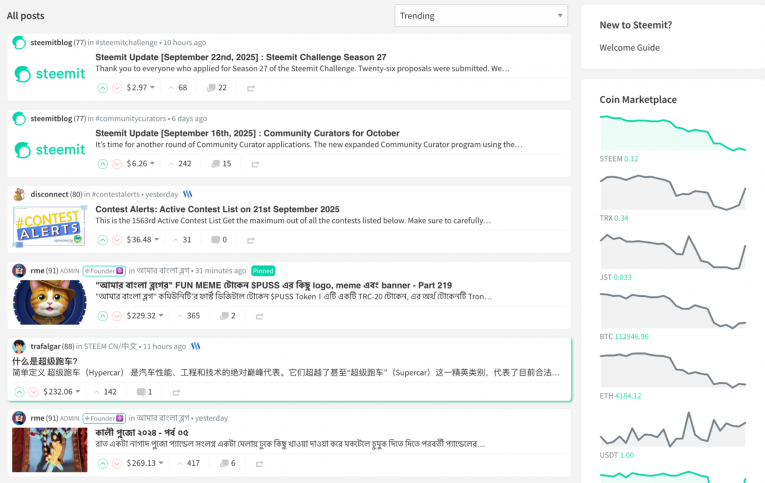

The above examples use likes, follows, upvotes, and their equivalents to confer value to content. However, some take quantizing value to its inevitable economic conclusion by allowing users to apportion value in cryptocurrency (Images 1 and 2 show that value in the dollar amounts that correlate to the value of the currency at the time of viewing). The two examples pictured below are Ecency and Steemit, decentralized social media platforms that both reward and incentivize their users by offering them the opportunity to earn cryptocurrencies with their content. The ability for users to earn money from their content is novel in a landscape where content is most often mined for data without recompense to the user. However, by introducing transparently quantified economic incentives, social relations become transactional by definition, and the status inequalities mentioned above become codified economically.1

Image 1:

Image 2:

4) To Experiment and Iterate in Decentralized Social Media

We need to determine if we can accurately apportion value at scale without quantifying it, or by quantifying it in significantly more people-centric ways. The more decentralized social media platforms mentioned above still use quantified metrics (likes, follows, etc.) to assign value and, in doing so, risk decoupling status from underlying quality.

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) have, in solving various problems of collective governance, demonstrated new ways to vote and apportion value. One example is quadratic voting, in which a voter not only chooses the direction of their vote but also the strength of that vote. In the case of social media, one could like a cat video and also a cure for cancer post and add an increased strength of like to the latter, for instance. However, quantifying value with greater precision will not remedy the negative effects explored in this post.

Decentralized trust systems could also offer a way forward. Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) allow people to trust one another without sharing personal information, and similar ways of “verifying” value without publicly quantifying it could help us develop value measurements that more closely correlate with underlying quality. Similarly, web of trust-based systems could help us trust one another without explicitly quantifying value. These and similar methods also mitigate bot and AI-bot disinformation and misinformation threats and could enable relations with AI bots without confusing them with human interlocutors.

While a corporate online world functions for our engagement, it is not designed to function for our benefit. In allotting value to individuals and groups within this sphere, we are doing so not for the better functioning of a society, but for the increased profit of shareholders. As such, the way in which we determine status through online value games undermines the positive functioning of status in society while exacerbating its worst traits. We may end up in a situation in which some of the least credible voices are granted the most credibility, the least pro-social actors are granted the roles of social care, and the least trustworthy among us earn the most trust. One could persuasively argue that this is already happening.

Not all of these ills can be laid at the feet of the current iteration of the Internet. Status attribution has functioned poorly prior to the creation of our digital meeting places and was and remains a knotty problem in efforts against bigotries of all kinds. However, the current ways in which we apportion value at scale, and the structures within which we evaluate one another’s competencies have the potential to worsen these tendencies far more than ameliorate them. Decentralized systems of trust might help us decouple our reliance on quantified, public metrics to determine value, but they haven’t done so yet. By experimenting and iterating on these systems, we will hopefully be able to find pro-social ways of conferring status online that take the inherent inequalities in status and align them more clearly with the public good.

SHARE