When One Company Owns Your Memory

Shaan Jain

Research Associate, Decentralization Research Center

Cover Image: Katerina Bolovtsova, via Pexels

Introduction

Search was once open, messy, and plural. Then PageRank turned discovery into a single chokepoint, and Google became the gatekeeper of the web. Social media promised connection, then collaborative filtering concentrated our attention on a handful of feeds optimized for outrage and compulsion. Both became monopolies, both rewrote society. Now, AI brings a new frontier: memory, the structured record of our lives.

AI assistance is quickly becoming a large part of our daily lives. Apple’s new release of Apple Intelligence brings on-device models to iPhone/Mac/iPad for writing tools, image generation, and a more useful Siri that can act in your apps. Google’s Gemini (on-device) reads what’s on your screen, drafts and summarizes text, and offers many more functionalities across Android. The same goes for every other company, folding assistants into their stacks—Microsoft with Copilot, Anthropic with Claude, startups with task bots, the list goes on.

These summaries, texts, and answers to questions big and small are being stored, and the industry has made it clear that long-term memory will be a defining capability of AI. OpenAI’s ChatGPT now draws on saved notes and past chat history to personalize future replies, and the push is clearly toward assistants that remember you over months and years. Sam Altman highlighted memory as a central direction for GPT-6; “people want memory,” he said, signalling a race to win by knowing you best. Anthropic just rolled out automatic memory for enterprise users. “Personalized AI” is the marketing phrase, but “personalization” also means your memory is being stored somewhere and, currently, it’s not with you.

Every prompt, click, and handoff becomes fuel for an agent’s memory of you: dietary restrictions from grocery orders, meeting rhythms from your calendar, tone and templates from your emails, and even spending patterns from receipts. At its best, that memory makes help feel effortless: it writes recipes to avoid your allergens, drafts messages for you, and can help schedule your life. But the same memory also tightens your ties to a particular product.

If years of learned context live inside one vendor’s silo, switching tools means workflow breakage, losing access to accumulated answers, and retraining your assistant from scratch. If your memory stays in the hands of the companies that currently house it, switching will feel like starting a new life every time you change tools. What’s needed is a neutral, portable memory layer that travels with the person whose memory it is.

First‑Principles for a Memory Layer

A durable and portable memory layer has to do more than simply store facts about a user. It must govern how those facts are created, shared, and forgotten. Without proper guardrails, context blends across work and home, shared inferences outlive their intended purpose, and users can’t tell which agent saw what or why. The principles below turn memory into infrastructure that serves the person first, separating contexts by default, revealing only what a task needs, producing receipts you can verify, and guaranteeing symmetry so any compliant assistant can read and write the same user-held record. That is how memory stays useful, safe, and portable.

- Context separation — Work, personal, and family vaults are isolated by default; crossing them requires an explicit grant.

- Minimal disclosure — Prove what’s needed for a task without exposing the underlying record.

- Purpose binding — Every access is tied to a stated purpose; no open-ended reuse.

- Time limits & revocation — Access expires by default; revocation works and is auditable.

- Transparency & provenance — Tamper-evident receipts show who accessed what, when, and why.

- Portability & symmetry — With consent, any assistant can read (and write) the same user-held memory, so switching remains viable.

Realizing these principles requires a shared, open, and interoperable layer of memory—standard schemas, capability‑based interfaces, and auditable provenance so assistants can read and write with consent without central custody.

Policy is Already Pointing the Way

The GDPR represents one approach to tackling the problem of data ownership and governance. It guarantees a right to receive one’s data “in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format” and to transmit it to another provider.

In the United States, policy signals are increasingly pointing in the same direction, even without a comprehensive federal privacy statute. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has identified dominant data advantages, interoperability barriers, and switching costs as key concerns in competition and safety. Former Chair Lina Khan stated that tactics like “self-preferencing and blocking interoperability are or should be unlawful,” and today’s FTC leadership is generally consistent with this direction on competition harms. Chair Andrew N. Ferguson warns that “platforms who collect taxes on innovators, or who maintain monopoly power by steering consumers away from innovative competitors,” threaten innovation and growth.

Portability and interoperability have long been regarded as foundational elements of robust, user-centred digital systems, and the baseline need for safe, transparent systems and competitive markets remains unchanged. The question is now how to align those needs with the products that end up in the hands of users.

We Can Enforce What Policy Intends

A neutral memory layer enables both interoperability and competition. Companies can still create the groundbreaking products that make them successful, but so too will users be able to turn to the option that works the best for them, and to switch should a better option become available. While the field is in development, there are already multiple roadmaps and case studies by organizations thinking about and creating these layers. These are two of those projects:

Introducing the Human Context Protocol

A position paper from researchers at MIT, Oxford, and Microsoft Research makes a simple case: give people a standard, portable way to express and govern their preferences, and require every assistant to honor it.

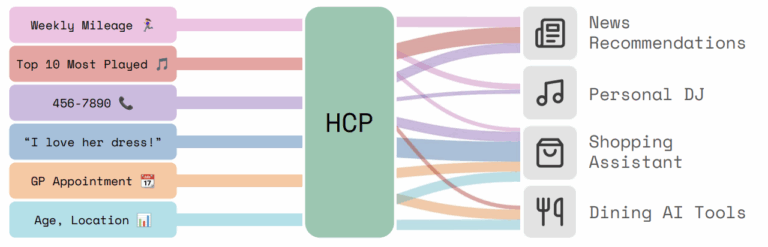

Introduced in this paper is the Human Context Protocol (HCP), a user-owned, secure, interoperable preference layer. Instead of letting platforms infer who you are from your history of clicks and watch time, HCP asks you to say what you want in natural language, then share only the parts you choose, with granular scopes, revocation, and auditability. Your preferences become legible, portable, and enforceable across all assistants, which lowers the cost of switching agents and counters the current boundary of proprietary memory (i.e., OpenAI owning your memory for GPT-6 implementation). As put in the paper, a Human Context Protocol “is not merely a technical convenience but a necessary foundation for AI systems that are genuinely personal, interoperable, and aligned with diverse human values.”

Figure taken from: Robust AI Personalization Will Require a Human Context Protocol

“Figure 1: Illustration of HCP. User preference data (generated by varied user activity) is moderated by HCP to consumer agents. Each agent obtains only the relevant subset of the user’s complete preference data. In the current ecosystem, agents themselves are built upstream on MCP.”

Memory-heavy assistants are arriving quickly. The convenience of familiar agents will lock us into one particular ecosystem, and innovation could stagnate. HCP presents a new option, offering a neutral layer where portability, scoped access, and receipts allow users choice and hold companies accountable for the products they create.

Case in practice: Mem0.ai

The largest players, OpenAI and Anthropic, have both rolled out memory features in their flagship assistants. Anthropic’s Claude now remembers your team’s projects and preferences across conversations, with separate “memory silos” for different workstreams. You can see and edit what the system remembers, but the boundaries and visibility are set by the application itself.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT also boasts persistent memory. Newly launched “Memory with Search” means that the model will remember details from your past interactions, like dietary preferences or geographical location for nearby restaurants, and then use those facts to personalize your responses. ChatGPT lets users manage and disable memory (with the “temporary chat” button), but, critically, data stored within these assistants is bound by their platform’s rules and technical limits. Neither platform is truly neutral; memory is architected to reinforce value within its ecosystem, not to empower the user with seamless portability or symmetric access.

A neutral layer sounds abstract, but a growing group of builders at a YC-backed startup called Mem0.ai is shipping a “memory for AI apps.” Mem0 extracts salient facts from your interactions and exposes them through SDKs (Software Development Kits) and APIs (Application Programming Interfaces). Its related OpenMemory project can run on your laptop as an MCP server, with a simple interface to inspect what is stored and to share only what a client like Claude Desktop or Cursor asks for. It demonstrates that memory can be a product feature that is visible and controllable. True interoperability still requires shared schemas, symmetric read and write rules, and commitments that every assistant honors. Without that symmetry, portability can be throttled. Mem0 is a concrete design that shows that memory can be exposed as a product feature. The Human Context Protocol treats memory governance as a public standard, which is how we lower switching costs across an entire market.

A New Default

There is a moment right now when a better default system can become the solution. Builders can ship products with scoped credentials, receipts, and exports by default. Consumers can demand that if their information is saved with an AI assistant, they should also be able to transfer it to a different assistant easily. Regulators must act decisively. Data portability and clear usage rules should be fundamental rights in the new digital age.

Skeptics will say people do not switch assistants often, so high costs are tolerable. The same was said about early mobile platforms and social networks. Switching was rare because it was expensive, and it was expensive because the platforms designed it that way. Portability is not only for those who leave, but creates incentives for a business to make you want to stay. If you can walk away without losing your memory, your vendor has to earn your business every day.

The companies building the GPT-6-era assistants are signalling a future organized around memory. Policymakers and users should make sure that HCP-style portability is the default. To prevent the future of one company monopolizing our digital memory, there must be built a switchable, interoperable layer that ensures that the people who create their memories get to keep them.

SHARE